Home » Philosophy » Aristotle–Understanding Happiness and Virtue

Aristotle—Understanding Happiness and Virtue

I experienced a profound crisis in my 50s. It didn’t involve career, or marriage, or health. I was fortunate in those areas. For several reasons, I lost confidence in my moral reasoning and beliefs about right and wrong, good and bad. The trend toward moral relativism unsettled me. Could much of what I believe be wrong? Then, several events caused further doubt about my moral foundation and, importantly, about whether what I believed was true. It was an emotional and intellectual crisis. It was a philosophical crisis, although I didn’t see it that way at the time.

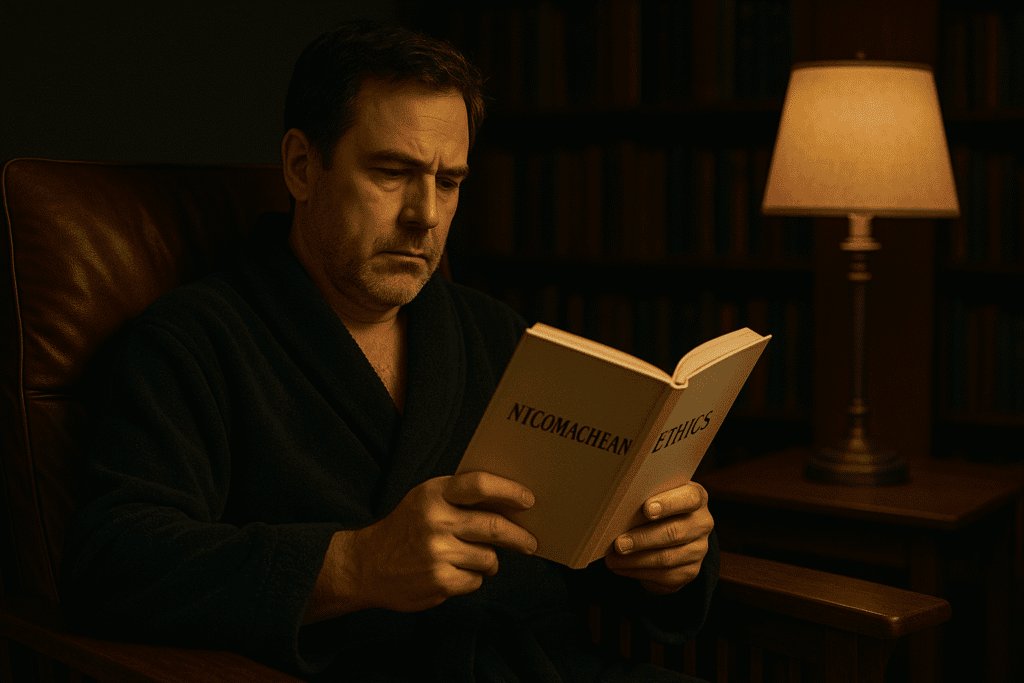

Then, at 2:30 one morning, anxious and unable to sleep, I picked up Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics and started reading. I knew immediately I had found help. Starting that sleepless night, reading the words of an ancient Greek, I began rebuilding my approach to living, my values, and my ability to thrive. It wasn’t an epiphany, where all is suddenly clear. And I didn’t experience a revolution where I discarded everything for a different approach. Instead, I found a solid and steady voice to guide me. After reading Aristotle, I realized I wasn’t completely lost, and I had found a guide to developing a richer and deeper approach to living.

Aristotle was difficult reading. I needed to read and think and then repeat the process. I looked at commentaries by others to help. It took time to understand the depth of his thinking. I realized how much of Western culture and thought rests on his ideas. Nicomachean Ethics is one of the few books I consider essential reading.

Following are the key ideas from Aristotle that stuck with me. Many are in Ethics, but I also draw on his other works. These ideas made a difference for me.

Happiness (Eudaimonia) is the Highest Good

Aristotle made happiness one’s life purpose. The idea is powerful. Refined and carried forward by many important thinkers over millennia, it ultimately shows up in the United States Declaration of Independence.

I have put happiness as my primary life goal since childhood. But I did not fully understand what it meant. I knew it was much more than feeling good. Aristotle provided the depth I needed. In doing so, it helped me gain confidence that happiness was the defensible goal for life. It provided the philosophical justification I needed.

Aristotle explains in Nicomachean Ethics that we should focus on the highest good, which is the good all other things aim for. He used the word “eudaimonia,” often translated as thriving. Thriving is being the best possible version of a human. Thriving is multidimensional and active. Aristotle sees thriving as acting in accordance with virtue and reason.

This broad understanding, reinforced by a similar view of thriving by the Stoics, stabilized, strengthened, and refined my primary goal in life. The next problem was how to get there. That is where virtue comes in.

Virtue as a System for Living.

Aristotle was my introduction to virtue as a framework for the practice of living. The field of virtue ethics grew out of his ideas. I always tried to live a virtuous life, but not in a thoughtful or deliberate way. In Aristotle I found a systematic treatment of virtue. Here was the essence of a well reasoned practical method for living well.

A problem I had with philosophy before reading Aristotle was that it seemed removed from the real world. It was a lot of theory that was hard to interpret and apply. But the virtues Aristotle laid out were theory applied to living. You could use them every day.

In particular, his view of wisdom as a virtue highlights the practical. It made learning how to apply virtues properly a key part of being virtuous. It made being virtuous a lifelong refining process, not just simple rules to follow thoughtlessly. A wise person knows how to be virtuous in different circumstances.

Equally important to me was his conditioning virtue on pursuing good. There are many virtues, courage and persistence for example, that could help achieve many ends. Previously this confused me. There are many bad people who are courageous and persistent. Aristotle clarifies that people must ground virtues in reason and apply them for noble purposes. Courage applied to bad ends is not a virtue.

Moderation and the Golden Mean

Moderation is key to understanding many virtues. Aristotle believed virtue often lies between deficiency and excess. The middle ground between extremes describes virtues such as courage, temperance, and pride.

For a virtue such as courage, one extreme is cowardice, where one avoids or runs away from a challenge. At the other extreme is foolhardiness. Here, people take unnecessary and pointless risks even if for a good cause. A courageous person takes the middle path, persevering in the face of danger but doing so wisely.

While Aristotle did not use the term “the golden mean,” it is a common description of the concept. Determining the right balance between excess and deficiency often requires wisdom and practical knowledge. The “mean” changes with the circumstances. It is a broad principle, not a simple yes/no rule.

Moderation is a constant guiding principle in my life. Its influence goes far beyond understanding virtue and guides me in many areas. “Moderation in all things” is a good aphorism that has worked for me.

I found extremes can be attractive. Society often admires extremes in athletes, entrepreneurs, and artists who are obsessed with being the best. But the hyper-focused, unbalanced approach to living often leads to bad or risky behavior and unhappiness.

Many times I consciously backed off seeking an extreme because I realized it would not lead to happiness. Conversely, there are examples where I had to correct deficiencies to move toward the mean. These occurred in all aspects of life, from relationships, hobbies, and work. It took wisdom to know where to draw the line, to determine the golden mean.

But in one area I remained stuck at one extreme until reading Aristotle. That is the balance between the individual and the community.

Humans as Social Animals

For years I approached moral and political theory from an individualistic perspective. It is my own well-being and happiness that matters. People should maximize individual happiness without harming others. Our institutions should make it easier for us to achieve happiness.

In reading Aristotle, I realized my thinking was too narrow. He argues humans are, by nature, political (social) animals designed to live in communities. We cannot survive as individuals. We evolved in a social environment where many of our abilities, such as speech and empathy, exist for social purposes. Our happiness depends on living productively with others. Part of our purpose as humans is to help others. Evolutionary biologists give scientific support, showing that humans evolved to be cooperative.

His arguments altered my approach to thriving. I understood better how my actions and pursuit of happiness affected others and vice versa. I had seen ideas such as duty and obligation as often infringing on individual happiness. Now I saw how important they are to creating a society that makes pursuing happiness possible.

It also exposed a flaw in the narrowly individualistic basis for ethical behavior. Many actions seem fine assuming they do not affect others. But it is nearly impossible to act without affecting other people. We interact with and rely on others so extensively that separating our actions from their effect on the community is difficult. This complicates moral reasoning. An action is good or bad based on how it affects us and everyone around us, even if the effect is indirect. That sets a higher standard for ethical behavior.

Of course, there is far more to Aristotle than these few points. And Aristotle was not the end of my journey. I had a lot more to learn. But these ideas on thriving, virtue, and our social nature were a solid beginning. There is good reason his teachings and ideas have withstood the test of time.

You may be interested in these essays:

Is Controlling Our Desires a Key to Happiness?

Return to Essays on How to Live and Table of Contents

Subscribe to my Substack Posts: Robin Gates Essays | Substack

Subscribe

0 Comments

Newest

Oldest

Most Voted

Inline Feedbacks

View all comments